Welcome to Latinometrics. We bring you Latin American insights and trends through concise, thought-provoking data visualizations.

Thank you to the 102 new subscribers who have joined us since last week!

Our MRR (monthly recurring revenue) is now $1733. Thank you to all of you that have opted for a paid subscription and supported our work! MRR grew 1% since last month.

Today's charts:

A look at fertility rates by country 🤱

The fastest growing Hispanic demographics in the US 🇻🇪

The share of income going to the 1% in each LatAm country 💰

Make sure you check out the comment of the week at the bottom!

Fertility Rates 🤱

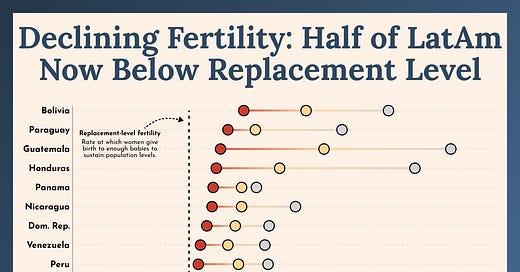

Peep the chart above—where does your country fall?

Last year, we wrote on declining birth rates in Latin America, and how the United Nations expected that by 2055 women in Europe would be giving birth to more babies on average than Latin American women. This week, we want to take a different approach, by focusing on specific countries and how their fertility rates give us a look into the future.

Fertility rate reflects the average number of a children a woman has in her lifetime. The replacement rate, meanwhile, is a fertility rate of just about 2.1, in which enough babies are being born to sustain current population levels within a given country.

As of the time of writing, roughly half of Latin America’s countries are still exceeding the replacement rate—critically, however, none of the four largest (Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, or Argentina) fall into this grouping.

Traditional logic expects that countries’ fertility rates will slow as they grow more developed due to a combination of better economic conditions and empowerment for women, lower infant mortality rates, and greater education and access to birth control.

Looking at the above chart, this seems to largely track, with the most-developed countries in the region – Chile, Uruguay, and Costa Rica – on one end while some of the least-developed – Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua – fall on the other end. Some of the most religious countries in the region, such as Bolivia and Paraguay, are also seeing higher fertility rates than many of their neighbors.

Notably, there are some unexpected results, whether that be Panama falling above the replacement rate or El Salvador falling below it.

The important takeaway, however, is that it’s completely normal for Latin America to slow down in population growth in the coming decades, just as it’s been seen in Europe and many of the wealthiest Asian states like Japan or South Korea. What’s more important is that the region reaches sufficient economic development and equity by this point.

Immigration 🛂

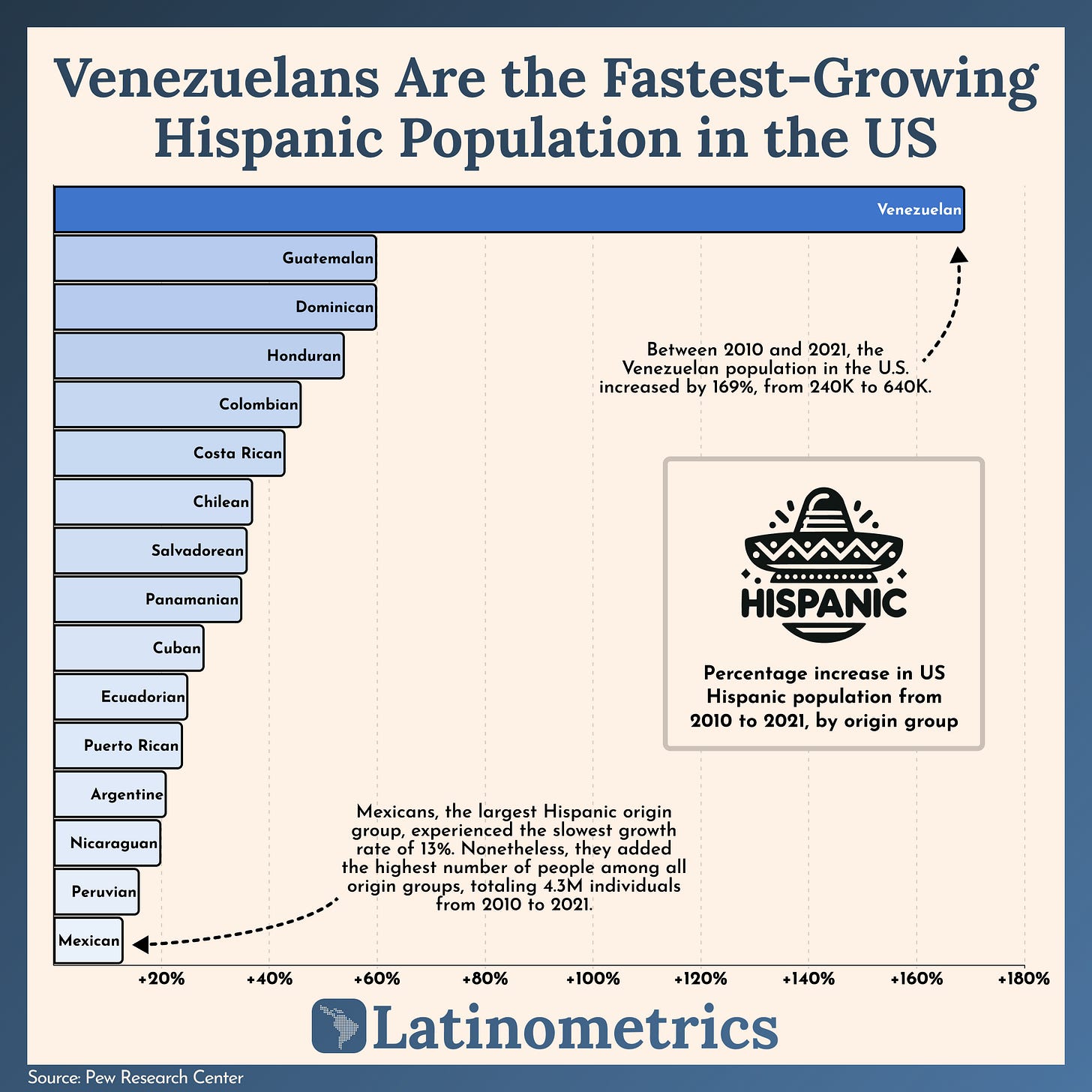

In the past few years, the US has seen an unprecedented number of migrants and refugees reaching its southern border. At the same time, a more long-term trend has been taking place for the past decade or so. The percentage of people detained at the US-Mexico border has become less and less Mexican.

Mexico now makes only about a third of apprehensions, which currently consist of a larger share of countries in Central America facing more challenging situations or, in the case of Venezuela, a full-blown crisis.

The word "crisis" has followed desperate Venezuelans, Haitians, and Central Americans all the way up to the States, where many, including governmental organizations, politicians, and media outlets, have called the explosion of arrivals a "border crisis."

The influx of diversity of different Latin Americans in the past decade is evident on our chart. Venezuelans living in the US have more than doubled in size from 2010 to 2021, with a 169% increase. The distinctive growth of this demographic stands out from the rest by an extensive margin (the next fastest-growing Hispanic group was Guatemalans, and their population grew by 60%).

The US is a country of immigrants, and Venezuelans are becoming a fundamental part of its culture. Despite the challenges of accommodating an unprecedented number of migrants, these Hispanic communities are finding and will find ways to integrate. As we've reported before, Hispanics have become an essential part of the US, as they alone would represent the 5th largest economy and have already become the majority in key states like California and Texas.

Income Distribution 💰

There’s no way to sugarcoat it: the pandemic has only worsened the problem of global economic inequality. And perhaps nowhere is this more true than Latin America, which has been named the most unequal region in the world by, among others, the United Nations and IMF.

But while it’s not breaking news that global crises further inequalities and concentrate more wealth in the hands of the rich, it may surprise you to learn where this is most the case.

The Dominican Republic, Peru, and Mexico are all among the most unequal countries in the world by WID figures, with the top 1% of each country earning between 25-30% of the country’s total income.

Yes, you read that right. The richest Mexicans earn over a quarter of the money flow in the country; the richest Dominicans, nearly a third.

The three countries rank only behind Mozambique and the Central African Republic by this metric, but the problem is far deeper throughout the region. Brazil and Chile both occupy painfully high spots as well, with around 22% of each country’s wealth being held by the countries’ richest citizens. This places these two major economies somewhere between Russia and a number of Gulf states that are either run by royal families or engulfed in civil war.

There are some expected results… and some surprises. Uruguay, which has emerged in recent years as Latin America’s success story, is the region’s most equitable society. That makes sense. But El Salvador falls far below its neighbors in terms of the share of wealth held by its richest citizens – a rare bit of good news.

Here at Latinometrics, we’re all about giving flowers to the countries and people growing Latin America, whether that be in Colombia or the Dominican Republic. But growth must include all people, not just the very richest. It can be a challenge to ensure development is sustainable and widespread – just ask recently-elected presidents like Gabriel Boric and Lula da Silva – but the only way the region will grow well is if everyone’s wealth grows with it.

—

That’s all for this week 👋

Comment of the Week 🗣️

Comment of the week, in response to our chart about real wage growth on LinkedIn

Join the discussion on social media, where we’ll be posting today’s charts throughout the week. Follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn, Instagram, or Facebook.

Feedback or chart suggestions? Reply to this email, and let us know. 😁

I agree the best way for a country to grow is when all the population has an oportunity to better their lives based on an improved education.